Experimenting with

MagicaVoxel

The best and worst part of being a designer is the fact that the technology you use to do your job never stands still. Lifelong learning is a part of the job, as is constantly upgrading your toolkit. Whilst the kit can be expensive (I'm looking at you £3,500 iMac), the buzz from learning a new skill or technique can't be beaten. You can guarantee at some point that a client is going to ask you to do that thing you haven't ever had to do before. In some cases you simply have to own up and manage the clients' expectations, explaining that what they're asking of you will probably require a specialist - and that specialist is not necessarily you. As a sole trader there's always a temptation to say yes to everything and figure out the how later, but burnout is real. Saying yes to everything is a slippery slope to exhaustion. It's something I learned the hard way a few years into running my own business and isn't something I'd like to repeat. Experience teaches you to pick your battles and manage your work-life balance as much as possible.

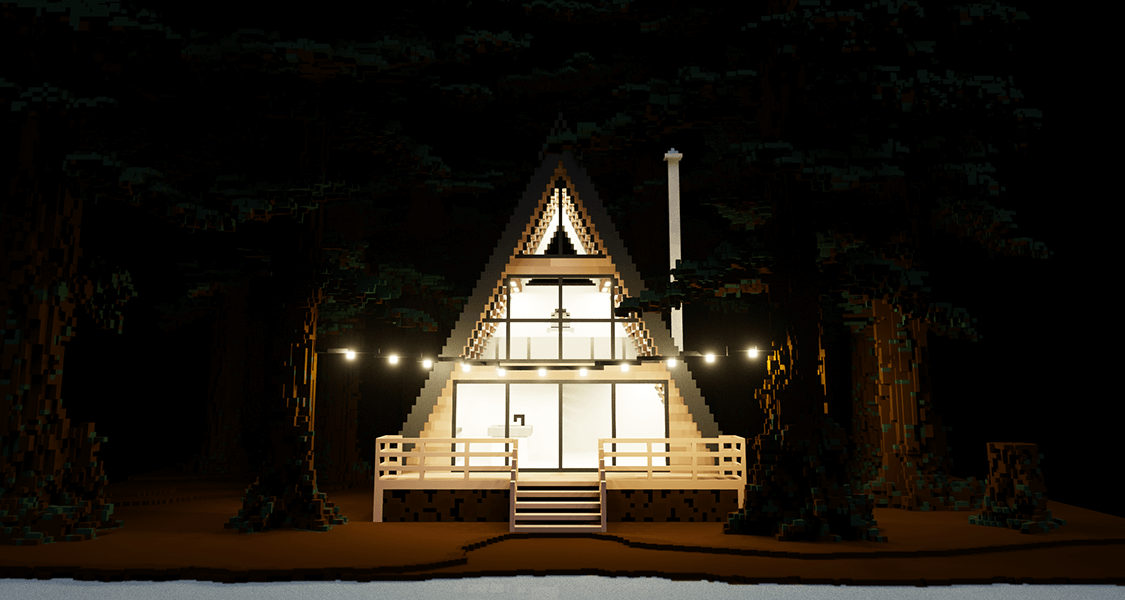

That being said, sometimes a client will ask you to look at something you've been meaning to learn for a long time, but just haven't had the excuse to do so. This happened to me recently when two long-term clients asked about my ability to render in 3D at the same time. One was a manufacturer of window blind components who had partnered with a major UK retailer to sell their products direct to the public, and the other produces components for the automotive sector. Both needed a way to render their CAD designs into photorealistic images that could be used in future marketing literature. Rendering in 3D is much cheaper than photography and often produces higher quality results. I was confident that I would be able to answer the call having spent some time working with 3D models for mockups, so I set about researching the tools and learning some new skills.

Adobe Dimension, Compatibility Issues, and Lots and Lots of Rendering

Working with 3D is not as difficult as it may sound and I quickly discovered that a lot of the skills I already had were transferrable to the 3D space. The similarity of Adobe's suite of applications was a major factor here. I spend the majority of my days switching between InDesign, Illustrator and Photoshop, so making the jump to their 3D applications wasn't a stretch. Neither job required any actual object modelling as both clients were supplying prexisting CAD files. I would only need a way to render materials, lighting and object placement. Adobe Dimension was the perfect tool for this and I was quickly able to assemble components and assign photorealistic textures to them in the 3D space.

A major stumbling block I hit upon early was compatibility, especially with the automotive manufacturer's CAD files. Not all 3D files are the same, so it is important to get a good understanding of the differences between filetypes and rendering methods. That way you can develop an efficient pipeline for your file management. A good file converter was vital and I ended up relying heavily on FreeCAD to create files that were compatible with Adobe Dimension. Before too long I had developed an efficient workflow and was able to render models of varying degrees of complexity and save my clients money on expensive product photography.

So where's the fun part?

Well, I was getting to that! We have to have some preamble, surely? I understand that as fascinating as automotive and window blind renders are, they're not that fun. And these blog posts have to have some fun stuff in them otherwise you're not going to bother reading them. So waffle aside, let's get to the good bit. The long and short of it is that having spent some time working within the 3D space, I'd been bitten by the rendering bug. I don't mind saying that I spend a fair bit of time playing videogames and I've always wanted to learn how to make them. Whilst it's never too late to pivot I don't think I'm in a position to shut down my business and start a game studio, as much as I'd love to. But there's nothing wrong with having (another) hobby, right?

Recently I have been playing a lot of indie titles and really love indie developers' ability to do a lot with a little. Often the games that they produce are better looking, infinitely more playable and a heck of a lot more rewarding than the majority of AAA titles out there. You can really feel the passion of the creator in titles like Cloudpunk, Kentucky Route Zero and the visually stunning Art of Rally (shown below).

To scratch this itch and maybe start on the road towards game development of some description in the future I wanted to find a simple place to start. Like the early days of most of my creative endeavours they lack any real direction other than an appreciation of what's already out there. I had played a couple of games that were built using voxels and liked the lofi, low resolution feel of the medium. So I decided I'd find out more about them.

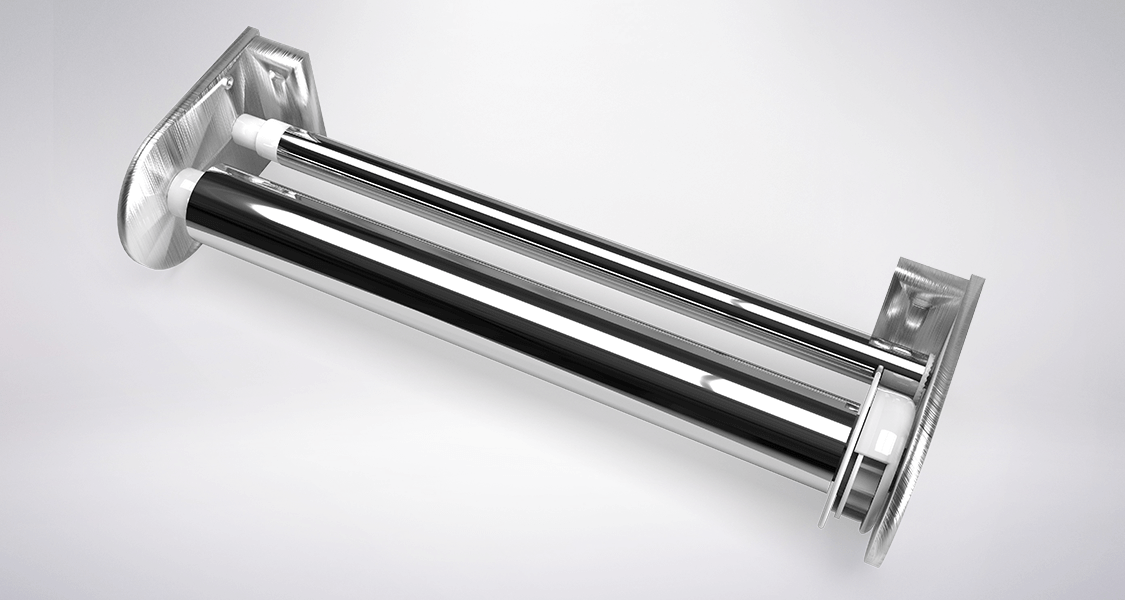

It was during my research that I discovered MagicaVoxel - a free to download voxel art editor. Creator ephtracy has put together an intuitive and powerful tool that has spawned a fantastic community of creators, all producing visually stunning voxel artwork. I have been well and truly bitten by the voxel bug and have already spent a lot of time learning how to model, light and render using MagicaVoxel. In fact, you've probably noticed a few of the models I've created on the homepage of this website. Much better to have a super cool pixelated version of yourself and your office rather than an ugly photograph!

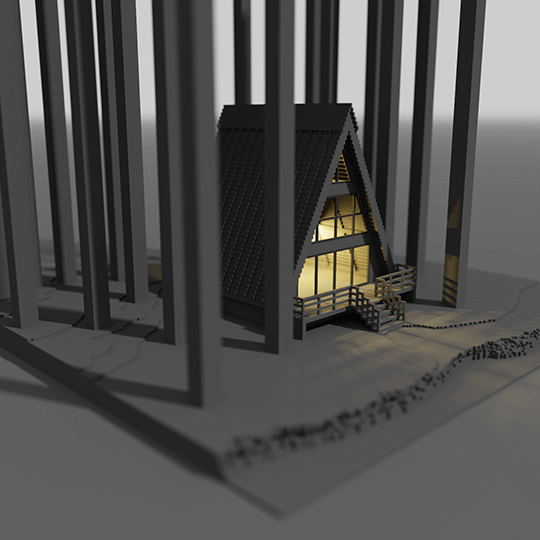

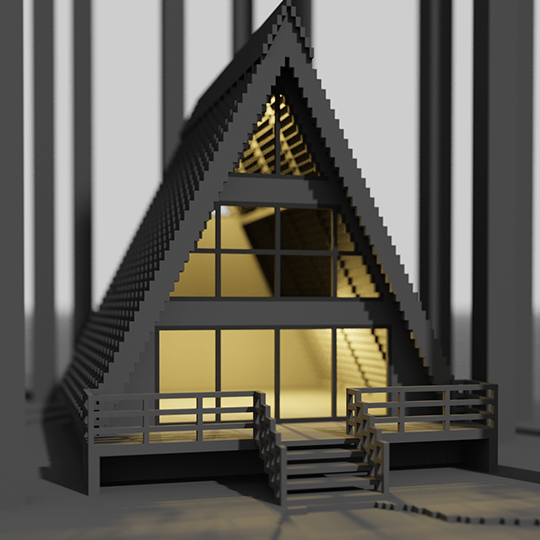

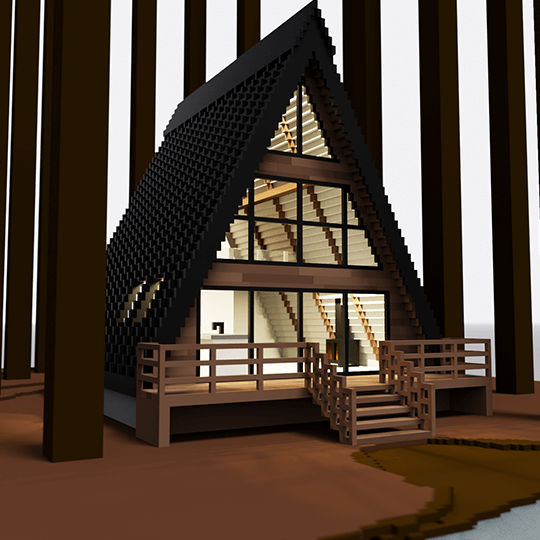

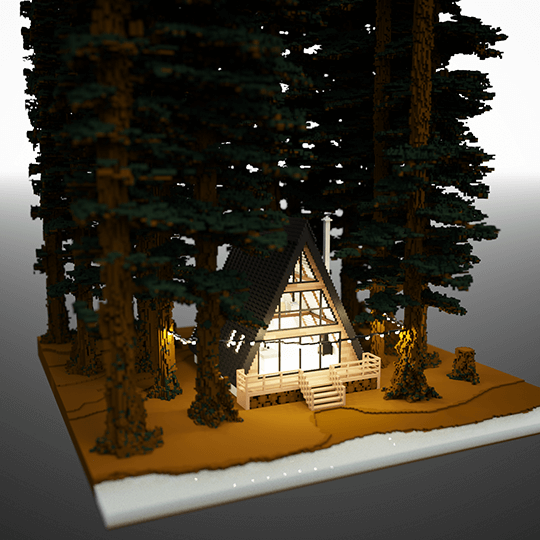

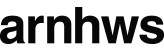

The A-Frame

As an exercise I decided to try and model an A-frame cabin in the woods using MagicaVoxel. It is a long-term goal of mine to build one for real one day so I thought it would be a fun, and reasonably complex, challenge to try and model one in this medium. Progress shots below show how I have been putting the model together, and you can start to see how it evolves in complexity as the level of detail increases. There is something rewarding about hitting the render button once the the model is ready. It really comes to life with good lighting and camera effects and has a cute, miniature aesthetic quality. I'm not sure what the next steps will be or if my adventure in 3D will lead to anything more, but it sure is a lot of fun to do so I'm going to keep on doing it.

Back to the Blog